I spent 10 days on the island of Moorea after Tahiti and it was an invited change of pace to move from a bigger, busier island, to one that felt more off of the radar. It’s only 20 kilometers north west of Tahiti, and about one-fifth the size but the differences between the two Polynesian islands are striking. Fewer tourists take the 30 minute ferry ride to visit Moorea; fewer visitors equates to fewer locals comparative to Tahiti which is probably because there are fewer jobs. Fewer people means fewer cars, less traffic — in the end it means that this place feels more secluded. When you are in the south pacific on an island, that feeling of seclusion augments the romanticism and mystique of the natural environment and native history. Everything feels more special.

Moorea can be circumnavigated in a car in a little over an hour — which is about 1/3 of the time it takes for Tahiti. The mountainous geology, scenic ocean views and variety of beautiful things to see are comparatively more concentrated; I found the destinations more accessible on here. You can hike over the center, mountainous mainland whereas Tahiti’s is largely inaccessible. The best beaches on Moorea are all accessible by driving up to them and parking. Everything that you want to see is easy to get to. I found this charming and reminiscent of the Azores — approachable and accessible to all types of visitors. Adventurer’s can go for long hikes, less mobile travelers can drive past magnificent mountainous vistas and take photos from their car’s window. All you need is a rental car.

Moorea is famous for its pineapple plantations; unfortunately the picking season is in December and the fields were mostly empty. Luckily roadside vendors were selling smaller pineapples all over the island and I took the opportunity to eat as many as possible.

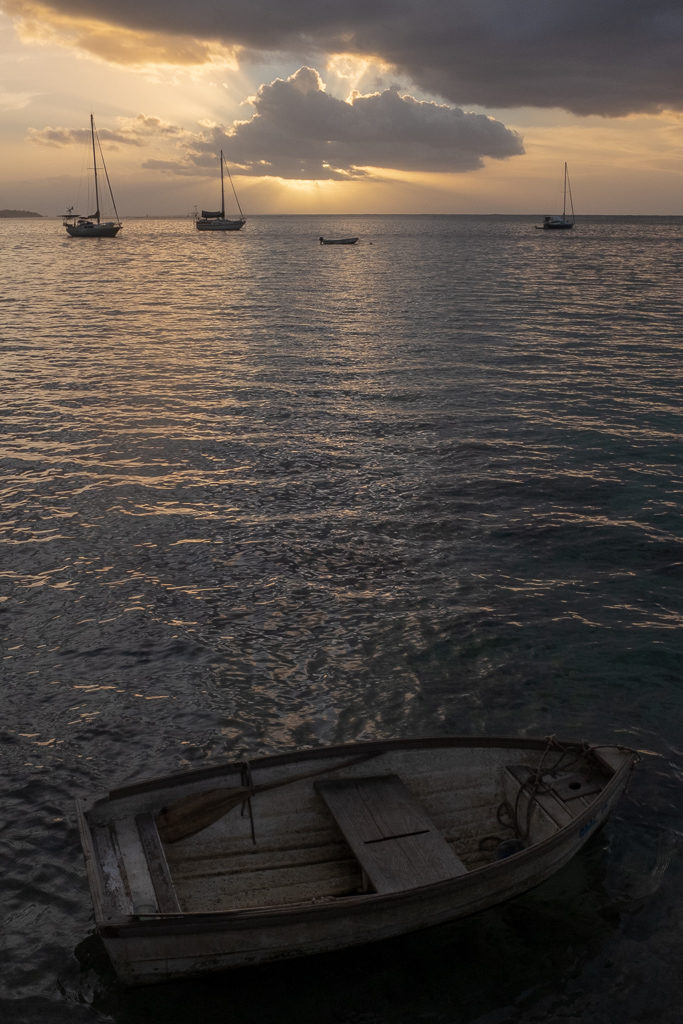

Owing to the smaller number of people on Moorea, the beaches were very comfortable – uncrowded, spacious with that sapphire water you expect from vacation booking websites. I took over 500 photos during my time there, many of them of mountainous skylines or beaches lined with towering, irrationally slender palm trees. It’s destinations like this that can make any of us feel like photographers — everywhere you look there’s something that wants its photo taken.

One of my favorite experiences on Moorea was discovering my love of vanilla. It turns out that even though I thought I already knew what vanilla tastes like, I didn’t. “An estimated 95% of ‘vanilla’ products are artificially flavored with vanillin derived from lignin instead of vanilla fruits” (source). “However, vanillin is only one of 171 identified aromatic components of real vanilla fruits” (source).

When I started smelling the dried vanilla beans offered by vendors throughout French Polynesia the difference between what I knew vanilla to be versus what it actually is was surprising. A fun artificial vanilla flavoring fact about: did you know that beavers have exocrine glands that secrete a substance that is recognized as the Food and Drug Administration as a generally safe food additive usually used as artificial vanilla or raspberry flavoring?

To my sense of taste and smell, real vanilla has a richer complexity that I find intoxicating. It wasn’t long before I found a homemade ice cream shop that used real vanilla beans. I became insatiably desirous of vanilla everything. I purchased vanilla seed pods to pull close to my nose to smell while driving, to sniff while puzzling over a work conundrum while staring at a computer screen, before going to bed at night. It turned me into an insatiable vanilla addict. It is a battle I fight to this day. I really must caution you never to discover real vanilla for fear it will instill in you also an unquenchable need for more.

After hypothesizing their inevitable existence in the area, I stumbled upon a shade-grown vanilla plantation. You might imagine my disappointment upon discovery that the vanilla plants would not be flowering for another few months. While the vanilla production process is highly manual and burdensome (the seed pods themselves take 9 months to grow) and involves curing of the ripened pods to release their aromas), the thought of being amidst an entire plantation of vanilla plants in full olfactory magnificence had me willing to sit down on the spot and wait for it to materialize. I’ve been researching how to grow vanilla via the internet subsequently and it seems achievable; the most prohibitive aspect necessitating a humid environment 10-20 degrees from the equator. Perhaps once I own a home in Colombia?